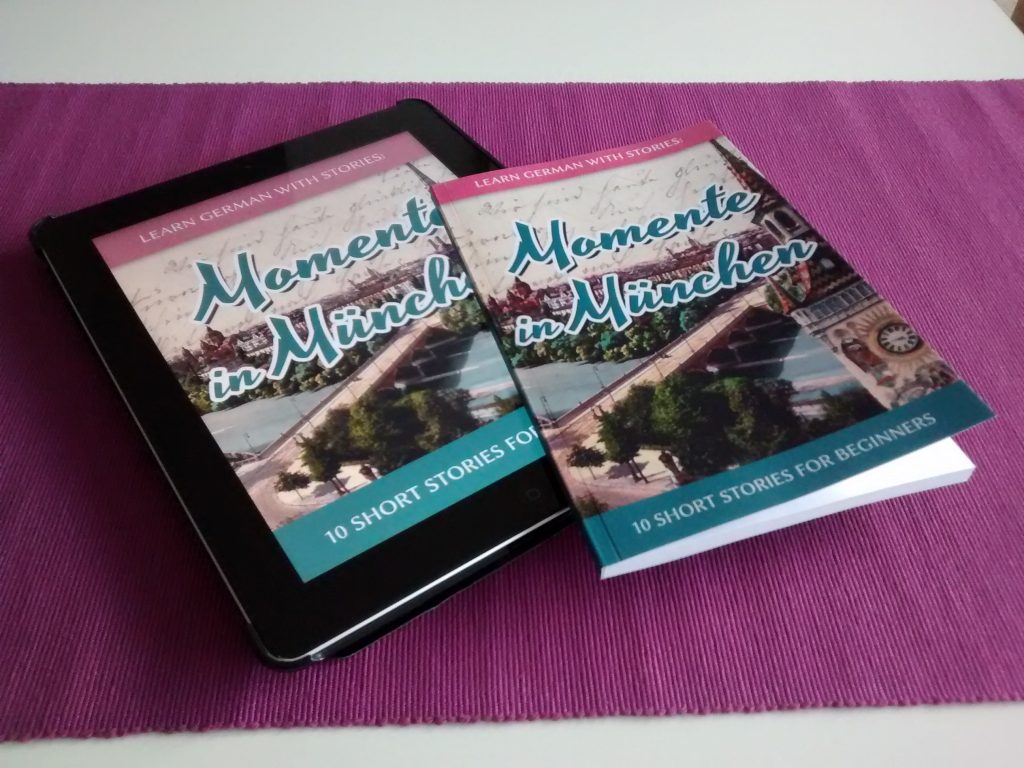

[drop_cap]I[/drop_cap] still remember the time I first laid eyes on the paperback edition of one of my books which had previously only existed as a digital edition. It was as if this book had finally become “real”, transplanted from the evanescent stream of on-screen appearances to an irrevocable manifestation in my own hands. Somehow, now that it was taking up space in three-dimensional reality, it seemed immediately more compelling, although content and cover were exactly the same.

What is the difference between a digital book and a paperback? Countless articles have been written about the tactile joy of turning pages, the comfort of search functions and libraries that fit in your pocket.

These are all features. But what is the difference in terms of being?

When we’re reading words on a page, parsing sentences and paragraphs, our mind conjures up alternate worlds, not only, but especially when it comes to storytelling. When we read a fairy-tale, a great fantasy epic or a gripping novel, we begin to inhabit a different space altogether, one where we see, hear, smell, taste and touch through the senses of the narrator, where we feel the pains and joys of characters and their relations, as if they were our own.

In that sense, books are travel-aids, private transport devices to different worlds and experiences. The format of a book should not be judged in terms of its physical properties, but in how far it supports or distracts from the journey unfolding in our minds.

When that heavy tome keeps slipping out of your hands and knocking into your chest, when your tablet is pestering you with notifications, then your experience is interrupted. When the typeface on the paper is too small, when the text flows unevenly on your e-reader, all this makes it harder to get lost in the story.

In short, a book is a means of delivering an experience, not an end in itself.

Despite cultural pessimists, who have always seen the end in every new beginning, the Internet and ebooks have not destroyed our reading culture. In fact, we’re reading more than ever. Status updates, comment threads, instant messages and listicles may not be what we traditionally think of as “literature”, but in a sense they’re all required reading.

The debate whether electronic texts are better than texts written on paper is a futile one. It’s like arguing about the color of ink Shakespeare and Tolstoi wrote in, instead of actually looking at their stories.

It shouldn’t matter where we read, but what and how. Whether I skim yellow press headlines on a mobile phone, tablet or pulp, it’s still the same old media manure. And vice versa, when I’m deeply engrossed in a great story, it remains a great story, whether displayed in pixels or burned into dead tree mush.

Recently, when I received the proof copy of the paperback edition for my latest book, I had an interesting moment. Opening the package, carefully sliding out the book and touching the fresh matte finish cover, I found myself completely underwhelmed, not by the book itself, but by its physical manifestation.

Despite myself, the first thought that went through my head was: “Oh, it’s that thing … from the Internet.”

And suddenly the tables had turned. Where once the physical object had seemed to be the true culmination of the thing on my screen, now the paperback was just another iteration of the real thing living somewhere in the cloud.