Question [paraphrased]: “I read that the Genitive case is going extinct in German, but it seems alive and well in some Netflix series and your books. What gives?”

That’s an excellent question!

First of all, it’s definitely true that the Genitiv is generally fading out of fashion.

However, it’s doing so in a very uneven way, i.e. in some use cases it’s almost extinct whereas in others it seems quite persistent, as you correctly noted. Sidenote: we’re mostly speaking about colloquial use here.

Since you mentioned Netflix, in season 2 of the German series “How To Sell Drugs Online (Fast)” there is a recurring joke where the protagonist Moritz (who’s a bit of a stickler) constantly corrects his friends’ use of the preposition “wegen.”

They’ll say something like: “Ich bin glücklich wegen dem Lottogewinn.”

And he’ll lean in, shaking his said: “… wegen DES LottogewinnS” – and they groan …

In other words, Genitiv after “wegen”, while technically correct (and always preferable in formal texts) just sounds weirdly stilted to many modern speakers, so we just opt for the Dativ instead.

The phenomenon of Genitivschwund (Fading Of The Genitive) is an oft-discussed subject among linguistics and has led to multiple publications (including criticisms) over the years, for example here or here.

Personally, I’ve always been fascinated by the research discipline of Sprachwandel (language change). There are many theories why languages change over time, such as efficiency of communication (not the same as laziness) or (a personal favorite of mine) the Invisible Hand Theory.

For the sake of this email I’d put it like this:

- Yes. Genitiv is fading out of fashion (in colloquial use).

- Some use cases seem to be more affected than others.

- My thesis is that speakers will generally replace the Genitive with Dative only when it is more efficient communication-wise. If dropping the Genitive has no real (or perceived) efficiency benefit, people are more likely to just leave it.

- Predicting this effect is difficult and has to be done on a case by case basis.

Hope that helps.

Question [paraphrased]: “The verb ‘anschauen’ ist listed in my dictionary as sometimes requiring the Dative and sometimes the Accusative case. So which is it?”

Gute Frage 🙂

Some verbs can be used reflexively (with “sich”) or in the non-reflexive way (without “sich”).

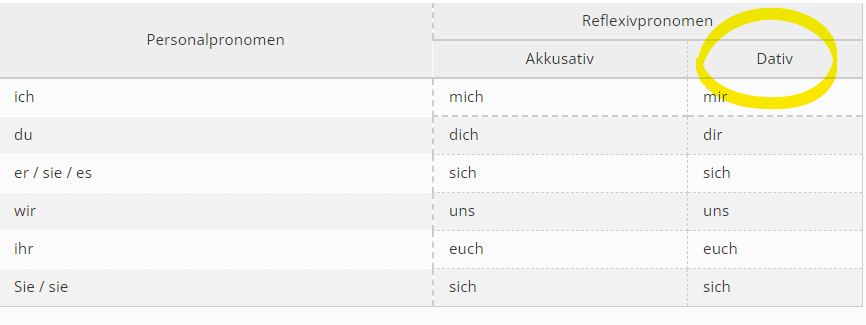

With reflexive verbs of this nature (sich anhören, sich holen, sich anschauen, etc.) you always have two objects:

a) the direct object (what the verb targets) – Akkusativ

b) the indirect object (the reflexive pronoun) – Dativ

Examples:

Ich schaue mir den Film an.

Du schaust dir den Film an.

Sie schaut sich den Film an.

Wir schauen uns den Film an.

Ihr schaut euch den Film an.

When you look at the table below you can see how the reflexive pronoun always gets the Dative case.

In the non-reflexive usage of the verb, the indirect object (Dativ) simply drops but the direct object (Akkusativ) stays:

Ich schaue den Film an.

Du schaust den Film an.

Er schaut den Film an.

Wir schauen den Film an.

Ihr schaut den Film an.

–